Art or Activism – An India Currents Cover Story

Art or Activism

By Sujit Saraf

In 2004, I staged a play that spoofed the Bhagavad Gita. Having studied the Gita closely for years, it had occurred to me that its subtle argument had been clothed in a theism that was completely unnecessary. I set out to correct the problem with a play that re-wrote the Gita, first by killing Krishna, then by having an atheist recite 16 new lines that captured the main argument without the religiosity that, to my mind, confounds the book.

The reaction was predictable. A professor at San Jose State in California sent around an angry letter, calling us “communists” and exhorting the world to put an end to our blasphemy in ways he was careful not to specify. A campaign was launched. Protesters gathered in the parking lot to hand out flyers saying “do not watch this play because it insults Krishna.”

There were heated arguments in the lobby. The police were called. The protesters dispersed. The play was staged. Our audience went home. We went on to do other plays. Our activism, as well as our protesters’, sparkled and died like a shooting star.

I cite this incident because the question of how seriously we should engage with “the issues” keeps coming up in my own theater company, Naatak.

A Spanish-language magazine once asked me what we thought of the raging immigration questions of the day. Pete Wilson’s Prop 187 had recently made news, as had demands for amnesty and border fences. What was Naatak’s opinion? she asked. It has none, I answered, because ours is a theater company and not an activist group. Is there a difference between the two? she asked.

There is.

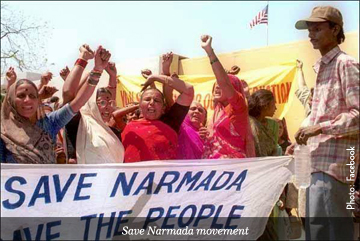

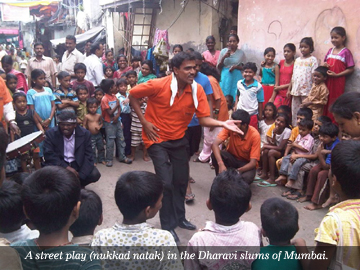

Rousing Passions

Theater activism is as old as theater, and is often conflated with it. I have indeed been a theater activist, of a sort. During the Narmada Bachao Andolan days in India, there was no dearth of street plays by activists. We gathered a crowd in the street by beating a drum and then played a middle-class family extolling the promise of the Sardar Sarovar dam—it would irrigate this many hectares, bring that much prosperity and create this many jobs, and the objection of a “few tribals” who would be displaced was mere posturing. Then we’d be informed that our own house was to be demolished to make way for a new highway, and we would rise up in vehement opposition. The point of the play was that many supporters of the Sardar Sarovar dam were NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard)-style hypocrites. It brought cheers from the audience. For that moment, they were united in opposition to the dam, however much their passions cooled after they went their way.

But of course that is not the whole story. Anyone who dwelt on the matter seriously would have to confront the nuances of the issue, such as the fact that all “development” lay more heavily on some than others and perhaps the solution lay in fair compensation to the ones affected more, combined with the near certainty that the compensation given to poor tribals would be unfairly low.

I don’t presume to know the answer, but I do know that a street-play could not begin to capture the complexities of the problem, let alone approach a solution. At best, it highlighted the problem in a simple-minded manner, roused a few passions that were quickly cooled when its casual audience dispersed, and struck a small, very small, blow for fairness.

Shock and Awe

This suggests a simple fact: activism is not art and activists aren’t artists. Activism has no room for nuance because it seeks to effect change through shock and awe, and an examination of both sides of the coin will dilute the activist’s commitment to her cause. Art, on the other hand, cannot afford to ignore nuance. It despises simple-minded shock and awe and is quite comfortable with half-loyalties and half-truths even if they render it toothless as an agent of social change. However effective The Communist Manifesto may have been in rousing the masses, it was not art. And so it is for theater—bad plays are often written with good intentions.

With this in mind, we chose art over activism in our theatrical productions. To some extent, the choice was made for us because of where we stage our plays and whom we show them to. The limited impact of Indian theater activism is further reduced once it is removed from India.

When the Babri Masjid was demolished in Ayodhya in December, 1992, I was in Massachusetts. A long meeting was held at the university by students and professors from India. Essays were written in local newspapers about “Hindu fanatics in India.” In the evening we took out a candlelight procession in the town square, marching silently in coats and mittens and caps, holding placards denouncing the demolition and shaking snow off our boots. Some passers-by stopped, some did not. None knew who we were, why we were marching, or where in the world Ayodhya was.

And it did not matter.

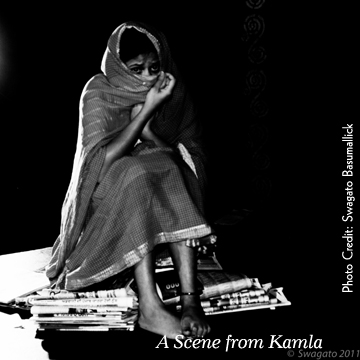

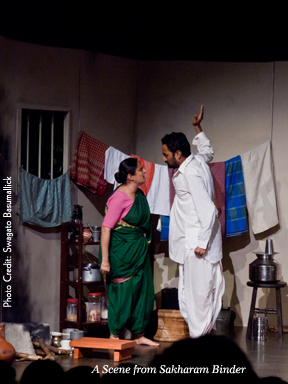

For all its theatrics, our activism was a harmless storm in a far-away tea cup. The issues that animated us for a day mattered not to our audience, and barely mattered to ourselves. When we staged Vijay Tendulkar’s Kamla, a blogger wrote that Naatak “tackles sex trafficking.” When we staged AsgharWajahat’s Jis Lahore Nai Dekhya O Jamyai Nai, some said we were “tackling” the post-partition violence in 1947 India. When we staged Sakharam Binder, some thought we were making a feminist point.

The Presumption of Influence

In all these cases, we were doing nothing of the sort. It would be silly and hypocritical to pretend that theater companies like ours had suddenly woken up to these causes and were exercised by them, after having given them little thought for much of their lives; it would be presumptuous to claim that a simple play, staged once and forgotten promptly, constituted an act that might change society for the better, or change it at all. Even the Dandi March, after successfully focusing the attention of millions on the salt tax, had to be followed by tortuous negotiations between Irwin and Gandhi to mean anything at all. Our plays were but feeble imitations of the Dandi March, and we had no desire or interest in following up.

In September this year, we will stage a play set amidst the widows of Vrindavan who find their lives upended by a sudden announcement that they will be repatriated to their homes in Bengal, in a misguided effort to “uplift their lot.” The play uses as its starting point a recent comment by Hema Malini, once Bollywood’s Dream Girl and now a Member of Parliament from Mathura. Visiting a widow-home in Vrindavan soon after winning the election, she said that there was over-crowding among the widows, and it would be nice if the states where they come from, primarily Bengal, could make arrangements to keep them there. The uproar that followed was vicious, partisan and short-lived.

For about two weeks, the widows became everyone’s cause célèbre. They had the right to live in Vrindavan or anywhere else in India, said assorted NGOs. They had been coming to Vrindavan for 500 years, said activists, so who was this newbie Hema Malini to question their residency? Left-wing politicians and West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee competed with each other in expressing concern. Some widows were taken to Kolkata to see Durga Puja and to meet the chief minister. Then the news cycle turned over and the widows were consigned back to their five-century oblivion.

Now, when we stage the play, some will think that we have “taken up the cause” of Vrindavan widows. This would be utterly hypocritical of us. Who are we to presume to do anything for these women when hundreds of activists are hard at work in Vrindavan? And where were we for 20 years while these activists were toiling away? Will we still be taking up this cause after our play has been staged and the next play is being planned? But of course not. Like all our plays, this is a work of art, not an instance of theater activism.

Think Small

This is not to say that I believe in “art for art’s sake”—or the kind of artist mocked by Sartre as “not satisfied with being useless, but wanting to trample on all utilitarian work.” From time to time, theater companies should provoke, incite, highlight an inconvenient truth as long as their activism is understood to be transient, which means it is not activism at all. So, when we staged Mataji, our send-up of Ammachi, the “hugging saint,” we weren’t launching a campaign against her empire of infantilism; we were merely pointing out what was obvious to us but somehow not to others.

This retreat from big pretensions is essential for an Indian theater company whose themes are often drawn from the other side of the world, whose members do not depend on it for their livelihood, and whose “causes” must necessarily change from one play to the next. Indeed, a guiding principle for an Indian theater company in America can be stated quite simply: think small.

A Natural Speak

There is another pressing question that Indian theater must answer before it spreads its wings in America: which languages should we stage our plays in? During my theater days in India, it was fashionable to do American and British plays, in English—we staged Sam Shepard’s True West and Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, neither realizing nor being told that, as Indians who had never left India, we could not possibly make sense of such stories, nor play those roles with any authenticity. I believe that a play should always be staged in its “natural language,” by which I mean the language its characters speak off-stage. This is not always easy to figure out.

Why was Girish Karnad’s The Dreams of Tipu Sultan being staged in languages like Kannada and English? I asked him this over tea at his home in Bangalore. Tipu himself would have spoken Dakhani, he replied, an Urdu-like language heavily influenced by Kannada, Telugu, Konkani and Marathi. Karnad could have written the play in Dakhani—he knows it well—but chose Kannada and English partly because the source material for the play, drawn from notes kept by a professor in Britain, was already in English.

So it isn’t always clear what the natural language of a play is, aside from the challenge of finding scripts that meet this narrow definition. There is the additional challenge of finding “our scripts” when we don’t really know what that means—is a historical Hindi play “our play” or a play set in modern Delhi? Or, must it be transplanted all the way to America to be truly ours?

The Future of Indian Theater

After 20 years of staging plays, I wonder: what might happen to Indian theater in America in the next 20 years? There are Indian theater companies, large and small, all over the country. Which of these will be around in 20 years? When San Jose Repertory Theatre collapsed last year, James Reber, its founder, cited changing demographics as one of the reasons.

When the Rep was founded in 1980, said Reber, San Jose was 74.1 percent Caucasian and 22.3 percent Latino, and its Asian population was miniscule. In 2010, the city was 28.7 percent Caucasian, 33.2 percent Latino and 31.7 percent Asian. This makes me wonder, perversely, if the same storms that sank the Rep might fill the sails of Indian theater companies in America and if they might evolve into mainstream organizations. If they do, will they be able to avoid the pitfalls of professional theater? After all, there are reasons other than demographics—such as an over-bloated budget—for the Rep’s demise.

Laurence Olivier once said that acting was “not quite the occupation of an adult.” Twenty years from now, I hope Indian theater in America remains stubbornly in the Brahmacharya station in life, refusing to grow up or get married or settle down, anticipating instead of reminiscing. As for the future Sannyasis of Indian theater, they could do worse than spend their days in an activity that is not quite the occupation of an adult.

Sujit Saraf

Sujit Saraf is the founder and Artistic Director of NAATAK. Over the last 25 years, he has written 10 plays and directed more than 20. His novel The Peacock Throne (Sceptre, 2007) was nominated for the Encore Award in London, and his third novel, The Confession of Sultana Daku (Penguin, 2009) is being made into a motion picture.